In This Edition:

The Larimore Qualities I Admire Most

What’s New On The West Side?

Subscribe!

The Larimore Qualities I Admire Most

“Loving and loved, a universal favorite, a universal friend, is T. B. Larimore.”

-- Silena M. Holman

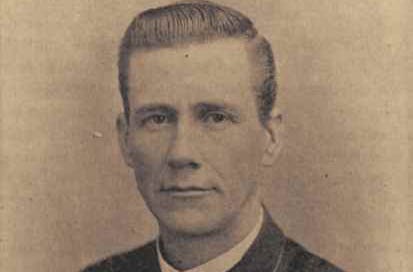

Theophilus Brown “T. B.” Larimore (1843-1929), was an enormously influential educator, preacher, and leading figure in the American Restoration Movement. Larimore was only twenty-seven years old when he began the work of building Mars Hill Academy, a school for which he served as the first president. 150 years later, I was privileged to fill his shoes and serve as president of Mars Hill Bible School, the living legacy of Larimore’s original academy. “Brother” Larimore—as he was often called by everyone who knew him—was a remarkable man, and some of the highlights of his story are worth retelling.

A Man of Gentleness, Kindness and Generosity

Larimore exuded a generosity of spirit, and that spirit became a central hallmark of the Academy he founded. Lee Jackson, a former Mars Hill student, reflected on the connection between the school and its founder:

On everything and everybody Brother Larimore seemed to have impressed his own personality to a very remarkable degree. He was held in personal admiration and affection by everyone; and, as a result, his gentle humility, kindly disposition and refinement of manner were reflected in teachers and pupils, and in all others within the range of the school’s influence. A spirit of fellowship and sympathy prevailed among all, and all were happy in their associations of friendship and Christian love.

F. D. Srygley, another Mars Hill Academy graduate, described Larimore’s gentleness of spirit:

There is a gentleness in his nature that impresses itself upon the churches he builds up, the pupils he teaches and the converts he makes…. Wherever he labors, he not only instructs people in the doctrine of Christ, but teaches and shows them how to receive, retain and cultivate the Spirit of Christ as well.

There was a magnetism to his personality that was steeped in the warmth of his Christian character. “It is hardly possible to associate with Brother Larimore and not be made better,” reported one contributor to the Gospel Advocate in 1901; “He is very greatly loved by all who know him.” “As usual,” wrote another admirer, “wherever Bro. Larimore holds a protracted meeting everybody falls in love with him.” Perhaps this is why one author in the Sherman Democrat in 1894 declared “probably no man has visited the city who is more universally admired.” That same year, F. D. Srygley offered a similar note: “Certainly no other preacher is personally known, respected, trusted, and loved by more people in a wider field than T. B. Larimore.” In 1904, Silena Holman summed up all of these sentiments in a single paragraph:

He is marvelously magnetic. To know him is to love him. To call him brother is a pleasure. He has hosts of friends, loyal and true. He is loved by men, women, and children, as few have ever been loved.

Among the tributes offered at the news of Larimore’s passing in 1929, friends and admirers claimed “he was the personification of love” and “the great Apostle of Love;” he was “the very embodiment of kindness, a living example of gentleness,” and “exemplified the grace of love.” They spoke of “his mild and gentle manner,” and praised “his peerless example of patience and deep humility of spirit, coupled with his unsurpassed godliness and brotherly love.” According to Mars Hill graduate F. C. Sowell, Larimore “was so gentle, kind, and good that one would feel that if everybody in the world were just like him, it would give one a foretaste of what heaven would be.”

In a sermon entitled “Christ and Christians,” Larimore set out the basic reason for his genuine love and kindness toward all of God’s people:

[A]s you treat Christians, so you treat Christ, and, so far as it bears on your destiny, it has the same effect as if done to Christ personally. If you hate a child of God, the Savior takes it as hating him; if you reproach a child of God, the Savior takes it as if you reproached him; if you do good to a child of God, it is as if you did the same thing to Jesus. All these things being true, I want to ask you this question: If we love the children of the living God; if we cultivate that love, cherish the tenderest and truest and purest love for the sons and daughters of the Lord Almighty, are we not thus loving Christ?

His loving kindness was often on display, and the world took notice. When a yellow fever epidemic swept through Florence, Larimore became heavily involved in the city- wide relief effort. In addition to joining hands with others, he also acted unilaterally to much acclaim. A writer for the Florence Gazette could not contain his appreciation:

This gentleman by his course during the late epidemic acquired a high position in the hearts of the people of Florence: When our people did not know where to turn for safety, and when many kind hearted country people would not permit a person from Florence to alight at their doors, Mr. Larimore welcomed all who came to him and furnished them houses at Mars Hill free of charge. Of the ninety persons who sojourned at Mars Hill during the fever in Florence: not one was sick or died, this speaks volumes for the health of Mars Hill. We wish Mr. Larrimore [sic] every success in his school. The Christian church should sustain it fully.

Larimore’s legendary kindness toward others came from two sources. On the one hand, he was timid, and his natural temperament involved unusual sensitivity. “He is of a tender, shrinking, sensitive temperament and feels so keenly unkindness,” wrote David Lipscomb, “that I feel for him most keenly when he suffers it.” On the other hand, Larimore’s motivation was also supernatural, rooted in his love for Christ; as he put it: “I cannot disappoint Jesus.” Just as Jesus and his followers taught Christians to entertain strangers, Larimore offered his home for any in need. During the summer break between terms in 1879, Larimore offered the following invitation to those seeking to avoid the summer heat:

[M]uch of our room will probably be vacant. If circumstances render it necessary or desirable for any of our Florence friends to seek a home here during the warm weather, as was the case last year, we desire them to consider themselves invited to do so. To such accommodations as our place affords, all are more than welcome.

Larimore’s kindness extended to young and old. He was especially fond of children, and the feeling was mutual. “The spirit of the man is so kind and gentle,” wrote one admirer in 1894, “that little children throng around him in swarms, just for a smile and a warm shake of the hand.” Ten years later, another biographer noted that Larimore spoke “always so plain, simple and gentle that little children understand him perfectly and love him devotedly.” “None can look into his face and doubt that he is a good man,” wrote Silena Holman. Larimore not only showcased a blameless life, but had “a gentle grace and dignity all his own.”

A Man of Peace

After some difficult experiences in youth, Larimore became a pacifist and remained one all of his adult life. But his stance against injury and retaliation went beyond bodily harm to include one’s spirit and reputation. “It is both a sinful shame and a shameful sin,” wrote Larimore, “that, ‘man’s inhumanity to man makes countless millions mourn;’ and nothing is more manifestly contrary to every principle of the spirit of Christianity or the revealed will of the Prince of Peace.” He continued:

He who, claiming to be a child of God, deliberately, willfully, maliciously and habitually seeks to injure the person, property, prospects, character or reputation of a brother, sister—any one of Adam’s race—proves, plainly and positively, that, there is at least one savage, satanic ‘wolf in sheep’s clothing’ still growling around, ‘seeking whom he may devour.’ Those who encourage him are partakers of his sin, and may expect to become subjects of his slander; for he who slanders another to you, will slander you to another. No one who loves the Lord will act thus.

Larimore sought to return kindness to all, regardless of how he was treated. “Brother Larimore evidently believes himself, under God’s providential care, called to work for the glory of God and the salvation of souls” wrote one Texas elder. “He never turns aside after the thrusts of his opposers but to treat them kindly.” This perspective led Larimore to focus on positive truths and to steer clear of negative criticism. “Brother Larimore was kind and gentle in his manner,” wrote H. Leo Boles;

It was not his style or disposition to engage in controversy or to be offensive in his preaching. He chose his subject and presented it in a simple, straightforward way without turning aside to notice any religious error. He preached the truth with earnestness and clearness and said little or nothing about any of the popular religious errors of the day.

Once when he was asked to publicly side with certain people and positions (to the detriment of others), Larimore wrote to calm such sentiment:

[P]lease let us clearly understand, solemnly agree and positively promise and guarantee that there shall be in our correspondence NO THRUST AT ANY PERSON, place or thing; but that EVERY sentence, sentiment and syllable shall be written in kindness, courtesy and love: our ONLY aim and motive being TO DO GOOD.

When Larimore issued a circular (entitled The Angel of Mercy, Love, Peace and Truth) in 1875, he introduced the work with the following editorial policy:

The Angel possesses not the slightest belligerent proclivity—not even in the latent or dormant state. It will avoid all unpleasant discussion and personal references. One harsh, unkind or unpleasant word will be sufficient reason for consigning to the flames any articles written for its pages.

“I am for peace,” the article continued; “my name is Peace—and no word of bitterness shall ever fall from my lips. Even in Self defense.” Two decades later, Mars Hill alumnus O. P. Spiegel wrote to Larimore, saying “your friends all admire your never speaking in self-defense, and never denying anything of which you are accused, and never accusing any one of anything.”

Larimore possessed a life-long determination to replace hatred and strife with peace, love, mercy, and kindness. ‘I am for peace,’ always,” wrote Larimore, “and ‘my manner of life from my youth’—the course that I have pursued for thirty-three years—has always tended to procure and preserve peace.” “Wherever he has been known for more than a quarter of a century,” wrote F. D. Srygley in 1894, “his name has been a synonym of gentleness, kindness, purity, and avoidance of everything approximating a wrangle.” In a private letter to Srygley, written at a time when Larimore was receiving harsh criticism, he wrote the following:

When I am gone, may it be said—truthfully said—of me: ‘He never tried by tongue or pen—never tried in any way—to injure any person, place, or thing; but studied, tried, and prayed to do all the good he could.’

A Man of Spirituality & Quiet Humility

Brother Larimore was highly educated, deeply admired, and widely known for his impressive preaching abilities. Yet in spite of this, Larimore was clothed in humility. In 1904, Silena Holman penned a short biography of the man, emphasizing this point:

He has gone with honor through two colleges and founded one; he is the admired hero of several popular books; and, as a minister of several popular books; and, as a minister of the gospel, he is regarded by thousands as second to none; but he never boasts, tries to display his learning, or seems to be conscious of his worth… He speaks evil of none, is envious of none, and considers himself no better than the humblest of his brethren.

Many well-known preachers of his tradition (before, during, and after his own period) were known for having a fighting spirit, with a penchant for debate. Larimore danced to a different tune, offering a quiet, tender, peace-loving approach. He was both humble and gentle, “never abusive, rough, or unkind,” and opted for listening kindly over public sparring. In his entire life, Larimore only engaged in one public debate, and that very early in his career. But Srygley’s description of the event foreshadowed Larimore’s future reputation:

The day passed pleasantly, without a discourteous or unkind word being spoken by either against the other. The audience was about equally divided in opinion concerning the merits of the doctrines advocated, but unanimous in the feeling that it was by far the most lovely and brotherly religious argumentation ever heard in that community.

According to Michael Casey, Larimore “exhibited an alternative to the debate tradition, an alternative which believed that preaching could transform culture, not merely oppose and attack.” Casey calls this a “spiritual, irenic, grace-oriented, culture-transforming tradition of preaching” which characterized the ministry of Larimore. Larimore replaced the fighting spirit—so prevalent among religious leaders of his day—with a peace-loving spirit. One writer in 1906 claimed “his sermons and his letters breathe a healthy religious spirit.” Indeed, Larimore exuded the spirit of Christ in his preaching, and it affected every church with whom he labored. “Our congregation is revolutionized,” said one church elder; “[t]he Spirit of Christ is manifest everywhere among us.” T. E. Tatum, writing in 1902, described the effects of a Larimore meeting in Weatherford:

In his matchless way Brother Larimore continues [to preach] clearly and fearlessly, yet courteously, kindly, meekly, humbly, and forcibly—giving offense to no one, but commanding the confidence, love, and respect of all who listen long enough to appreciate the spirit of the speaker, it being so similar to the spirit of the Master whom he so diligently serves.

Larimore believed that preaching the story of Christ with a gentle spirit could inspire and transform a generation of Christians to be more spiritual. Indeed—his approach inspired an entire tradition. “[B]y the life he lived and the gentle nature of his teaching,” wrote J. M. McCaleb, Larimore was able “to deepen the spiritual life of many.” G. C. Brewer once claimed that when the stress and strain of the world tempted him to embrace doom and gloom, he would open a book about Larimore or read a sermon by him: as a result, the world would get brighter, souls seemed more precious, and the love of Christ seemed clearer.

A Man of the Word

Larimore was a man of the Book. Once in 1894, during a protracted meeting in Sherman, Texas, Larimore was asked what works he would consult for preaching. He answered, “the Bible, Webster’s Dictionary, and the Bible—these three, and no more.” Where does he find subjects and materials for his lessons? “The Bible is full of them,” wrote Larimore; “It’s treasures are simply inexhaustible.” I see new beauties in the Bible every day,” Larimore continued, “and am simply astonished at the sweet, sublime simplicity of God’s eternal truth.” A follow up question, wondering if he would ever “exhaust the Bible themes, and thoughts, and truths,” received an amusing reply: “Yes, when the swallows drink the ocean dry.” A sermon delivered during that meeting provides further evidence of this bedrock principle. Larimore declared,

We believe the Bible. I may not fully understand it, and may make many embarrassing blunders in trying to preach it; but the Bible, the whole Bible and nothing but the Bible is our faith. Every syllable in the Bible is a part of our belief; therefore, [it is] as utterly impossible to quote one syllable of sacred scripture against our faith, as to fire a cannon at itself.”

Mars Hill was founded on a deep love and reverence for the Bible. It served as more than a textbook for incoming pupils, but the source of true knowledge:

A good, well-printed, well-bound copy of the Bible was presented to each pupil when matriculated, the Bible being justly regarded as the greatest of textbooks; and every pupil was expected to recite at least one lesson in the Bible every day. Indeed and in truth, our school and its curriculum were founded on the Bible and all our pupils and teachers knew they were expected to study the Bible and treat it with due deference and respect.

A Man Leaving Minor Matters Alone

With an open Bible in hand—whether in the classroom or in the meetinghouse—Larimore would engage in what he called “Gospel preaching,” or simply “preaching the Word.” By these phrases, Larimore meant what one of his former students described as “the Bible in its sweet simplicity.” Larimore once declared that throughout his life, he “tried to preach the word and let minor matters alone.” His deep love for what was revealed in Scripture defined forever Larimore’s conviction to avoid “untaught questions” left unaddressed in Scripture. In an 1897 article, Larimore explained his approach:

Of course, the purest, wisest and best preachers may have their hobbies, opinions, personal preferences, and, possibly, even prejudices, but ‘the Word of the Lord’ ever, and these never, should be preached. Sinners should be taught to become Christians; saints should be taught how to make their ‘calling and election sure,’ and all should be earnestly, tenderly and lovingly exhorted to abandon all evil, and walk in the light of God’s eternal truth. Ever believing, and never doubting, that gospel preaching and Christian loving and living are the greatest needs of the age that now it, I practically knowing absolutely nothing about or of any of the things—untaught questions among us—that are disturbing the peace of Zion, and never taking part in any row or wrangle, always, to the extent of my ability, just simply ‘preach the Word.’

Larimore once reminisced that he and his Mars Hill students “studied the BIBLE,” and “studied to know the Word, and tried to do the will, and walk in the way of the Lord,” which had nothing to do with “theories, opinions, and speculations of men:”

During all the seventeen years that the responsibility of presiding over Mars’ Hill College rested upon me, not seventeen seconds were wasted there on questions that ‘do gender strifes.’ We respected the divine command and reminder, ‘Foolish and unlearned questions avoid, knowing that they do gender strifes.’ We were always perfectly satisfied with ‘what is written,’ and therefore, by conscientious convictions, avoided all pernicious, ‘untaught questions,’ and fruitless, unprofitable speculations. ‘Thus it is written’ always satisfied every soul and settled every question among us.

Larimore claimed, and Srygley confirmed, that “the distressing, disintegrating questions” swirling in the air, invading Christian periodicals, and dividing churches, were neither asked, taught, “heard, thought, or even dreamed of” at Mars Hill. F. D. Srygley recalled a conversation that took place in the classroom, when one of the students asked Larimore where they should stand on a divisive issue that was filling the pages of Christian periodicals at the time. “Better not stand on that question at all,” replied Larimore; “stand upon Christ and him crucified. If you must do any thing with that question, sit down on it. It is not a good thing to stand on.”

A Man of Unity

The theme of unity figures prominently in Larimore’s extant sermons and writings, throughout his life. When Larimore was a new Christian, very early in his twenties, he was asked to preach his very first sermon. He chose as his text John 17, and titled the lesson “Christian Union.” Fifty years later, Larimore still considered this profound theme as central to his life and ministry:

I am still working for the fulfillment of that sacred prayer—for unity, peace and harmony… I believe no man, woman, or child who knows me will say my teaching tends, or ever has tended, to either produce or perpetuate discord, dissension, division, or strife… I have never encouraged the wrangling and strife that have cursed the cause of Christ, dividing churches and alienating friends. I have always earnestly contended for union, unity, peace, and harmony in Christ Jesus, our Lord.

Larimore believed the Spirit of Christ was at odds with a factious spirit interested in controversy, division, or party loyalty. In a letter describing things that discouraged him most in ministry, Larimore spoke of “envying, strife, and divisions,” along with “hatred, discord, and dissensions.” He mourned over a “lack of love, liberality, gentleness, goodness, faith, meekness, temperance,” along with a lack of “forbearance, forgiveness, patience, politeness,” and “prayerfulness” among those claiming to be followers of Christ. At years end, 1895, Larimore penned his annual new-year letter to Srygley, listing a few of his “life rules;” heading the list was a self-admonition to “be kind,” followed by calls to meekness, humility, gentleness, politeness, patience, courteousness, and unselfishness.

In religious matters, Larimore declared, “I propose to never stand identified with one special wing, branch, or party” but rather with all of God’s people. In fact, Larimore spoke of his “irrevocable determination” to avoid being a partisan among Christians. “I believe it to be MY DUTY,” wrote Larimore, “to be, in no sense, a partisan in any thing: to engage in no dispute, row or wrangle with any one.” Others took note that Larimore succeeded in this desire. Larimore is “in no sense a partisan,” noted Silena Holman in 1904; “he never participates in any of the wrangles and disputes disturbing the Churches of Christ. His life is, in every respect, spotless and pure. No one who knows him doubts his honesty, sincerity, purity, or integrity.”

This bedrock principle stemmed from a meek and gentle spirit resting in God’s mercy and desire for unity. In a private letter to Srygley, Larimore wrote:

I do not pitch into my brethren who do not do exactly as I do, or understand every thing just as I do, for two reasons: 1. I can understand how it is possible for them to act correctly and still not always do exactly as I do. 2. I love my brethren, and, long, long ago solemnly resolved to never go to war with them, or, rather, against them. It seems to suit some good brethren to dispute with each other, but it does not suit me.

Larimore called himself an “extremist” when it comes to avoiding anything and everything that causes “strife and division” among Christians. Larimore once write that he was “by both nature and practice, averse to discord, division, and strife, and in favor of union, unity, and peace.” “My earnest desire,” wrote Larimore in another letter, “is to keep entirely out of all unpleasant wrangles among Christians.” He concluded this line of thought with the following words: “I propose to finish my course without ever, even for one moment, engaging in partisan strife with anybody about anything.” Listing his motivation for such a stance, Larimore reminded his readers that “of the seven things Solomon declares to be an abomination unto God, the crown of the climax is ‘he that soweth discord among the brethren.’”

Keeping out of divisive disputes did not lead Larimore to cut ties or cut off association. Instead, for Larimore, it meant fellowship with all brothers and sisters in Christ who shared the central truths of the Christian faith. “The thought” of wrangling over matters of dispute “is revolting to me,” wrote Larimore. “To do good, I must love my brethren, and never refuse to fellowship them—ANY OF THEM—simply because we do not always understand all questions exactly alike.” Why did Larimore feel this way? His student and biographer, F. D. Srygley, expressed the point well: “No man has a right to make a test of fellowship of any thing which God has not made a condition of salvation. No man should be denied fellowship in the church on account of any thing which will not deprive him of admission into heaven.” Larimore expressed the same point in these words:

When Bro. Campbell took my confession, on my twenty- first birthday, he questioned me relative to none of these ‘matters now retarding the progress of the cause of Christ.’ While thousands have stood before me, hand in mine, and made ‘the good confession,’ I have never questioned one of them about these ‘matters.’ Shall I now renounce and disfellowship all of these who do not understand these things exactly as I understand them? They may refuse to recognize or fellowship or affiliate with ME; but I will NEVER refuse to recognize or fellowship or affiliate with them—NEVER.

In 1894, Larimore engaged in a 5-month long protracted meeting in the bitterly divided town of Sherman, Texas. So moved by his preaching, the elders of one church published a glowing review of his work:

[H]is able presentation of truth, by his non-partisan spirit, his meekness, his Christian charity, his love and gentleness manifested throughout this long siege for both saint and sinner alike, and his determination to preach the gospel of Christ, and persuade alien sinners to obey the commands of our Lord and Master, come into his fold, and be simply Christians—‘only this, and nothing more’—and by his masterly manner of disposing of queries propounded to him, always answering pleasantly, politely, and tenderly, as though addressing a little child, always exhibiting the true spirit of the Master, Brother Larimore has endeared himself to this congregation in bonds of love that can never be broken.

Larimore avoided any words or actions that led to “dividing churches and alienating friends.” He proposed to preach for any church where he thought he could do the most good, and to avoid derogatory terms for Christians, such as “anti’s” (to his right) or “digressives” (to his left). “I concede to all, and accord to all, the same sincerity and courtesy I claim for myself, as the Golden Rule demands.” This attitude was put on display during the Mars Hill years.

Larimore’s 1875 circular—The Angel of Mercy, Love, Peace and Truth—ran for seven months; in each issue, Larimore set aside two whole pages to advertise periodicals with drastically different stances on divisive issues of the day. Larimore added, “we heartily commend them all,” and offered his own circular free of charge to anyone who would subscribe to five of the advertised works.

Such a stance drew criticism. In an article both defending and criticizing Larimore, David Lipscomb opined that Larimore’s “gentle and meek manners” stemmed from his “nature of nonresentfulness” making “it is almost impossible for him to enter into a controversy with people.” “[K]nowing his temperament,” opined Lipscomb in another article, “I never expect him to aggressively oppose anything. He is not built that way.” But Larimore refused to change course:

Criticise freely brethren, if you wish; but do not hope to provoke unpleasant controversy with me. THIS YOU CANNNOT DO. When my final farewell to the world I have said, no one shall truthfully say, ‘By his death I have lost an enemy’; but be it carefully cut, in characters of truth, by request of those who love me, on the cold white stone that may cast its shadow on my lonely, gloomy grave, ‘THE WORLD HAS LOST A FRIEND.’

On one occasion, Brother Larimore was called into a meeting by those hoping to procure a condemnation from him concerning the actions of another, involving a disputed practice. He received harsh criticism for not making a public stance in such a way that would denounce and alienate those on the other side of the issue. According to F. B. Srygley, “He listened quietly, and when they were through he thanked them and departed.” On another occasion, Larimore finished preaching and asked if anyone in the audience wished to add anything. One listener stood and began to take issue with Larimore, spoiling for an argument. “Is that all?” asked Larimore; “then let us stand and be dismissed.” Stories of this nature appear throughout his life.

Reviews of Larimore’s approach are diverse—even among his supporters. Some were apologetic, noting “he was timid, and did not speak up as quickly as some have done, but his purpose was good.” Others saw a certain genius (as well as genuine kindness) in Larimore. S. P. Pittman offers a compelling interpretation:

Silence was more convincing than argument, and kindness than repartee. It was his conviction that the surest way of combating error was by preaching truth…I am convinced that long after the professional debater has been forgotten T. B. Larimore’s name will still be found upon the pages of history.

Despite his criticisms, Lipscomb—like so many others— came to admire and appreciate this aspect of the man, praising and promoting Larimore’s sound and persuasive preaching. “I have said of Brother Larimore,” wrote Lipscomb in 1910, “he comes nearer reproducing the teachings of the Bible in his preaching than any man I know. The sermons are, of course, good and true, and the manner of presenting them in Brother Larimore’s style, so attractive to the multitudes.” Larimore, true to his nature, wrote lofty, moving descriptions of Lipscomb on more than one occasion, including the memorable obituary tribute in the Christian Standard upon Lipscomb’s death. Larimore remained, forever, a loyal and devoted friend. It was his nature to do so.

Throughout his life, Larimore maintained his friendships with Christians on every side of religious divides, preached for churches that differed from one another on contentious issues, and wrote articles for journals associated with differing sides of the widening gap among restoration movement churches and leaders of his day. He was added to the editorial staff of the Gospel Advocate, and wrote a regular column for them for in his later years. In 1916, one writer for the Christian Standard bemoaned the clear, pronounced division of the churches by citing two books claiming to list all the preachers in the movement. Only Larimore appeared in both books. Larimore’s picture also appeared in the Disciples yearbook until 1925. It remains a remarkable curiosity that Larimore could be claimed, loved, admired, and eulogized by regular members as well as noteworthy leaders on either side of contentious issues, in all three branches of the Restoration Movement.

A Man of Singular Focus: Christ Crucified

When pushed to assess what lens Larimore used in assessing central biblical truths and matters of highest religious importance, the answer is glaringly obvious: Christ and him crucified. For Larimore, to “preach the Word” was to avoid untaught questions that “do gender strifes” and instead, simply “to know nothing, save Jesus Christ, and him crucified.” “I am for CHRIST,” Larimore continued; “and I believe I can do more for him, his cause and humanity without meddling with these ‘matters’ than otherwise; hence I let them alone, and just simply ‘preach the Word,’ ‘the gospel of Christ,’ ‘the power of God unto salvation.’” Upon hearing the news of Larimore’s death, James H. Sewell penned a memorial article in the Firm Foundation, emphasizing just this point:

I remember when as a youth my heart would thrill to his powerful and eloquent presentation of the simple gospel story. I noticed one thing then, and have ever since, that the burden of his message at all times was Christ. Other preachers often discussed many and various theological subjects, but not brother Larimore. Christ crucified, Christ raised, Christ exalted, Christ our tender loving Savior, was the burden of his heart and of his preaching.

This emphasis on Christ as the central figure and focal lens for reading and preaching Scripture figures prominently throughout Larimore’s life. At Mars Hill, Larimore and his boys “were blissfully ignorant” of divisive issues splitting churches, wrote Larimore; instead,

[a]dmiring the spirit of him who said, ‘For I determined not to know anything among you, save Jesus Christ, and him crucified,’…we sang—‘Go on, ye pilgrims, while below, In the sure path of peace, Determined nothing else to know But Jesus and his grace.’

As Larimore approached his golden years, the story was the same. “Those who have known Bro. Larimore for years know the kind of preaching” one can expect, wrote V. M. Metcalfe; preaching that begins and ends with “the same loving story of the cross.”

Throughout his life, Larimore eschewed all other interests and concerns for the sake of Christ. “We are not living, longing, and labouring for gold or worldly glory,” wrote Larimore to missionary J. M. McCaleb, “but to love and to be loved, to bless and to be blessed; hence, to do as much good as possible ‘while the days are going by.’ We belong to our friends, to humanity, to Christ and his cause.”

A Man for Others

At the close of an open letter dated July 10, 1897— published in three Christian periodicals—Larimore summarized his single-minded devotion:

I shall certainly never retaliate. I shall simply do as I have ALWAYS done: ‘love the brethren’; be true to my convictions; endure as patiently as possible whatsoever may come upon me; go when and where I am wanted and called, if I can; carefully avoid all questions that ‘do gender strifes’ among God’s people; ‘PREACH THE WORD’; try to do MY WHOLE DUTY, and GLADLY leave ALL results with HIM from whom ALL blessings flow.

I find much to emulate in Brother Larimore. I hope you do as well.

This article is taken from my book “The Mars Hill Story: 150 Years of Love, Mercy, Peace & Truth.” You can order copies of this book (complete with references) by reaching out to Lori Tays at Mars Hill Bible School (e-mail: mhbs@mhbs.org). Three lectures taken from the book appear on the Life on the West Side podcast (Season 2, Episode 41, Episode 42, and Episode 43). Available on all podcast platforms.

What’s New On The West Side? Summer Series

We are enjoying our annual summer sermon series. This summer, we have asked some of our favorite preachers and teachers to offer “their favorite sermon.”

The summer series is available for live stream on Wednesday evenings a 6:30 PM or can be accessed later on facebook or YouTube. If you are in the middle Arkansas area, we would love to have you join us in person. I’ll save a seat for you.

Subscribe to Life on the West Side

My name is Nathan Guy, and I serve as the preaching minister for the West Side Church of Christ in Searcy, Arkansas. I am happily married to Katie and am the proud father of little Grace. You can find more resources on my website over at nathanguy.com. Follow me: Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and YouTube.